The words “Obama” and “disaster” go together all too well these days. To name just a few, there’s Obama’s Middle East disaster, the Obamacare disaster, Obama’s economic disaster, and Obama’s Europe disaster, including Putin’s annexation of Crimea and the refugee crisis sweeping the continent — a crisis triggered by Obama’s Middle East disaster.

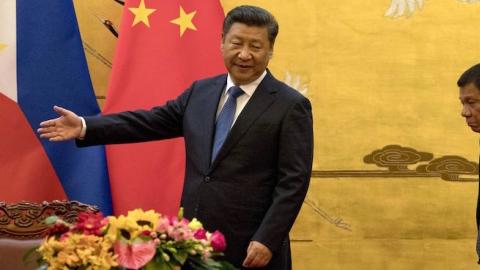

And now we have Obama’s Pacific disaster, which may have cost us America’s oldest ally in the region, the Philippines. Its president, Rodrigo Duterte, has been on an anti-American tirade since the G20 summit in early September. He’s denounced Obama to his face as a “son of a bitch” and canceled any future joint military exercises with the U.S. “America has lost,” he’s been quoted as saying, meaning we’ve lost out to the other great power in the Pacific, China. Duterte has just finished up trips to Beijing, to court Chinese president Xi Jinping, and to Japan, where Duterte said it was time for all foreign troops to leave his island nation — including the handful of planes and 200 personnel we sent to our former air base at Clark Field to monitor Chinese moves in the Pacific’s hottest hot spot, the South China Sea.

Granted, Duterte is an acknowledged nut case. Granted, too, U.S.–Philippine relations have had their ups and downs, with previous low spots including the Fernando Marcos years and President Corazon Aquino’s closure of our bases at Clark and Subic Bay in 1991. Still, Douglas MacArthur must be somersaulting in his grave. The idea that the country for whose protection and then liberation he dedicated so much of his life; the country whose soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder with ours to fight the Japanese army to a standstill on Bataan in 1942, and then hailed MacArthur as their savior when he kept his promise, “I shall return,” in 1944; the country that U.S. Special Ops troops have helped to save from al-Qaeda-affiliated insurgents since 9/11 — the idea that the Philippines would abandon its treaty alliance with the United States to join up with China, a nation with which Manila has been feuding for years, would seem outrageous, even contrary to nature.

But Duterte has good reasons for being upset. This summer an international arbitration court ruled against China in the Philippines’ dispute in the South China Sea, a stiff rebuke to Beijing’s claims of sovereignty over that busy international waterway. If Filipinos thought this would get the U.S. to firm up its support for the Philippines and other countries bullied by China, and do more than just sending out one or two Navy vessels to promote “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea, they were disappointed. Instead, the inaction from Washington was deafening. Duterte’s pullout from future military exercises, and his advances toward Beijing, signal a man who is fed up with U.S. weakness — and a nation that’s looking for a power relationship that increases its security rather than otherwise.

There’s a Filipino saying: If you are threatened by an elephant, hire another elephant. Duterte and others hoped the U.S. would be that elephant in dealing with China’s drive for regional hegemony. Instead they got a mouse.

They’re also not alone in sensing the strategic shift. Australia has slipped into neutral gear in the South China Sea, saying it won’t participate in any joint naval exercises there. Japanese officials worry that U.S. weakness in dealing with China will mean Beijing’s plans for turning the East China Sea into a Chinese lake may be unstoppable.

What’s the reason for American weakness? It was Secretary of State Hillary Clinton who first unveiled the Obama “pivot to Asia” strategy back in 2010. The rationale was that, as our contingency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan wound down, America would start devoting its time and resources to bolstering our allies against an increasingly militarized and aggressive China.

In fact, apart from setting down a Marine outpost outside Darwin, Australia; sending four littoral combat ships to Singapore; and adding a few more naval aid patrols, the vaunted “Pacific pivot” turned out to be more rhetoric than reality. The Obama team has evidently hoped that by not provoking China in the South China Sea and elsewhere, they can get Beijing to be more cooperative at a broader multilateral level, such as helping to fight climate change. It’s a fantasy, of course, but detachment from reality is the hallmark of this administration. It’s also threatening to unhinge the American alliance system in the Pacific.

What happens now? Our next president must reverse Obama’s disastrous course. The answer to dealing with China is linkage, i.e. making it clear that bad behavior in the South China Sea will have adverse consequences in areas where China has real interests, such as economic and diplomatic ties.

But for now, the path to Chinese hegemony in the Pacific is wide open. It’ll be up to the next president to close it down — before the next waterway Beijing lays claim to is Pearl Harbor.