The downfall of Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro serves as another powerful reminder to the world: China’s campaign for global dominance is not confined to the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea or Indo-Pacific trade routes.

It is global in design and opportunistic in method. In that strategy, Latin America, especially Cuba and Venezuela, serves as strategic platform and strategic distraction: a forward operating theater for intelligence, propaganda and influence operations meant to erode U.S. leadership while insulating the Chinese Communist Party from what it fears most, i.e., regime instability driven by global resistance to Chinese aggression, “peaceful evolution” and political defeat at home.

Economically, Latin America supplies Beijing with what it wants: resources, capital investment opportunities and terrain for infrastructure development that can bind states to China through debt, dependency and political leverage.

The deeper strategic value lies in Beijing’s primary objective: using the region to mitigate, diminish and ultimately displace American influence in its own hemisphere. Its methods are explicit. China uses capital to replace or sideline Western-led institutions such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank.

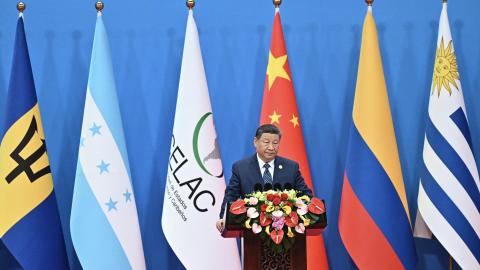

It promotes China-centered integration schemes such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States and the China-CELAC Forum, building a regional architecture where Beijing becomes the convening power and Washington becomes, at best, a distant outsider.

It wages political and propaganda warfare by backing anti-U.S. rogue regimes, above all Cuba and Venezuela, turning them into ideological and operational outposts.

Cuba is a frontline base in a long-running intelligence war. For nearly three decades, China has used Cuba for eavesdropping and military training, with U.S. intelligence reportedly aware of Chinese operations there as early as 2001.

After the Soviet collapse, the Castro regime lost its patron. Beijing seized the opening, transforming Cuba into a frontline anti-American station.

Beijing and Havana signed a series of agreements, some open, others secret, modernizing Cuba’s obsolete Soviet-era weapons and telecommunications. This was not symbolic solidarity. It was the infrastructure for a hostile mission.

The logistics of that mission are equally revealing. Chinese arms and equipment have been shipped disguised as commercial goods, primarily by COSCO, the Chinese shipping giant.

The shipments intensified after April 2001, following a collision between a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft and a Chinese interceptor near Hainan, an incident that the CCP’s supreme leader, Jiang Zemin, used during a subsequent visit to Cuba to secure new spy agreements. The covert pipeline surfaced dramatically in March 2015, when Colombian customs boarded a 28,000-ton COSCO vessel en route to Cuba and found an undeclared cache of Chinese arms: 99 rockets, 3,000 cannon shells, 100 tons of military-grade dynamite and 2.6 million detonators, manufactured by Norinco and concealed under declared merchandise. This was not routine commerce. It was covert militarization.

Nor is the target vague. The CCP’s eavesdropping from Cuba focuses on Florida, a dense hub of U.S. military command, training and space capability: three of 10 U.S. combatant commands (CENTCOM, SOCOM, SOUTHCOM), the Navy’s 4th Fleet, major naval aviation and pilot training bases and dozens of U.S. Air Force bases, alongside premier space research and launch facilities.

Intercepting communications among these nodes yields insights into how the United States trains, coordinates and plans for global conflict — information of immense value to a regime preparing a global counterstrike.

In this framing, Cuba is no relic of Cold War nostalgia. It is a Chinese listening post and staging ground 90 miles from the U.S. mainland, aimed directly at America’s capacity to operate globally. Venezuela plays a more openly aggressive role: an anti-American political spearhead and potential flash point designed to consume U.S. attention.

On Dec. 2, 2023, the bicentennial of the Monroe Doctrine, Mr. Maduro dramatically announced his plan to invade Guyana, a move framed as a strategic distraction designed to dilute U.S. focus from China’s aggression in the Western Pacific and beyond. Meanwhile, Beijing deepens military and security ties: fighter jets and missiles to Venezuela, military training and joint exercises in the jungles and cities of Venezuela; weapons and war equipment sold across the region; intelligence efforts targeting trade and technology secrets; and pressure to control choke points such as the Panama Canal while cultivating Nicaragua and Guatemala as alternatives for an isthmus route.

Taken together, Cuba and Venezuela form two pillars of a single design: Cuba as the spy and military node, Venezuela as the political-military destabilizer. Both operate within a broader architecture: economic dependency, institutional displacement, coalition-building and security cooperation meant to uproot the United States as the leading rival of the CCP regime.

Yet Beijing’s approach rests on a dangerous miscalculation.

The CCP treats the Monroe Doctrine as a declaration of American retreat, an inward-facing hemispheric obsession that can be neutralized by building influence south of the Rio Grande. The Monroe Doctrine was never isolationist. At its core, it was an expression of American cosmopolitanism, an outward-looking commitment to prevent Old World malign forces — European colonialism, medieval monarchy and later communism — from taking root in the New World so that a free and independent hemisphere could contribute to global peace and democracy.

The United States has never been content to be only a hemispheric power; it is, has been and will remain a global power because its security and ideals demand a global horizon.

Here, Beijing repeats Imperial Japan’s fatal pre-Pearl Harbor miscalculation: the belief that America will accept an aggressor’s sphere of dominance and withdraw.

Japan imagined the United States would tolerate a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The CCP similarly assumes that by entrenching itself in Latin America — through CELAC platforms, capital displacement of Western institutions, eavesdropping bases in Cuba and proxy destabilization via Venezuela — the United States will accommodate, hesitate or shrink from global responsibility.

That assumption is not merely wrong; it is also strategically reckless. American leaders may have been willfully indolent for too long, but the structural reality remains: a United States that understands its role will not accept hostile installations in its hemisphere as the price of peace, nor will it abandon global leadership because Beijing plays for distraction.

China’s Latin America strategy is therefore not an exotic subplot. It is a frontline component of the CCP’s global contest: to bind economies to Beijing, to undermine U.S. influence, and to use rogue regimes, especially Cuba and Venezuela, as platforms for intelligence, military cooperation, propaganda and crisis manipulation.

If the CCP believes this will confine America to a defensive crouch, it has misunderstood American power and American purpose.