1. Adaptation: The New Source of Military Advantage

The United States military has long relied on technical and industrial superiority to achieve advantage on the battlefield. During World War II, American mass production helped Allied forces overcome geography and a late start to defeat the Axis powers. During the early Cold War, US forces used their lead in nuclear weapons development and production to deter Soviet aggression. And after the Soviet Union reached nuclear parity, the Pentagon turned to stealth and precision-guided weapons to establish an edge over Warsaw Pact militaries.2

US forces used information-age technologies to sustain their lead after the Cold War ended. Low-observable aircraft, computer networks, and guided munitions helped the United States and its North Atlantic Treaty Organization allies succeed during Operation Desert Storm in Iraq and Operation Allied Force in Kosovo.2 In this unipolar era, US military and civilian leaders believed they could deter future aggression as long as they fielded more advanced versions of these systems.3

This belief led to program requirements that relied on analysis to predict future military challenges and technological opportunities, rather than feedback from current operators. Such an approach was logical when the US military was unrivaled and defense technology was mainly the purview of national governments and specialized companies.

But those conditions no longer hold. The technologies that yielded the precision strike era are now widely proliferated, as some forward-thinking analysts predicted.4 Long-range precision weapons, including one-way attack (OWA) drones, are now a core element of every national military and transnational paramilitary group. For example, Houthi rebels and their Iranian sponsors tested US Navy missile defenses in the Red Sea for more than a year with a combination of indigenous anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles, as well as OWA maritime and airborne drones.5

The character of warfare is also changing. As more actors acquire militarily relevant technologies, they develop new concepts of operation fitted for their environment and goals. This includes surgically employing precision weapons, cyber operations, and electromagnetic warfare in non-combat situations to change conditions in their favor without provoking an outsized response from the target’s allies. The Russian and Chinese militaries and Iranian proxy forces have used these gray-zone tactics to gain territory and influence during the last decade.6 By blurring the boundary between peace and war, gray-zone operations create sustained, sometimes militarized, confrontations.

Instead of military capabilities evolving slowly in peacetime and intensifying in war, tactics and technology are now continuously changing. This dynamic is not unique to twenty-first-century warfare, but computerized military technologies have allowed forces to instantly share lessons from each interaction and have intensified the speed and scale of move-countermove cycles.7

The pace of military competition becomes more severe when gray-zone operations boil over into combat, as in Ukraine. Drone designers operate on innovation cycles of a month or less and expect that any breakthrough they deploy might only work once before the enemy copies or counters it.8

The move-countermove cycle is accelerating for traditional weapons as well. Russian forces recently adjusted the flight profiles of their Iskander ballistic missiles to evade Ukraine’s US-supplied Patriot air defense systems, necessitating costly and time-consuming upgrades.9 And recent drone incursions into Poland and other NATO countries are forcing the alliance to adapt its surveillance networks and field new countermeasures.10

Therefore, in modern conflict the source of military advantage is shifting from possessing the most sophisticated technologies to possessing a superior ability to evolve concepts and capabilities.11

The US Department of War (DoW) will need to establish organizations and processes that exploit the insight that adaptation trumps performance. Rather than looking for generational leaps in capability akin to nuclear weapons, precision strike, or stealth, the Pentagon needs teams that can adjust the characteristics or programming of systems, the composition of systems of systems, and the integration of new and existing capabilities at high tempo.

But sustained adaptation is not the DoW’s strong suit. Despite more than a decade of reforms to government acquisition processes, the Pentagon still cannot field systems that take advantage of technical advancements or tactics at the pace and scale routinely seen in commercial products. This failure is not due to insufficient investment in defense research and development (R&D), which remains a multi-billion-dollar enterprise. Instead, the DoW struggles predominantly because it does not exploit commercial R&D, which dwarfs governmental efforts, and does not pursue acceptable solutions for near-term needs.

Defense acquisition officials are often to blame on both counts. In general, they are reticent to fully exploit new authorities, such as other transactions (OT), to prototype and procure new military capabilities as if they were commercial products. While program managers often use OT authorities to speed contracting, they still fall back on existing government system requirements, which demand specialized solutions rather than what a vendor can quickly assemble or build. Acquisition officials also have been slow to adopt the middle tier of acquisition (MTA), which bypasses traditional requirements development to address near-term operational problems.12

In part, program managers avoid new acquisition approaches due to a perceived lack of flexibility from service leaders who are responsible for establishing system requirements. Nearly every current Pentagon acquisition program emerged from a predictive analysis of future need with little consideration of the cost or time necessary to realize the envisioned capability. Program managers face a gauntlet of paperwork and briefings to adjust requirements and reduce technical or schedule risks.

New Pentagon reforms are addressing this roadblock. In a November 2025 memo, the US secretary of war (SECWAR) eliminated the joint requirements process and ordered services to streamline their own requirements processes.13 Going forward, the department will focus more on solving commanders’ key operational problems (KOPs) and less on addressing predicted future needs. With these changes, future programs should address near-term challenges or opportunities and rely on less highly specified requirements, affording program managers more flexibility in implementation.

The SECWAR issued a separate order in November 2025 that directed the Pentagon to substantially reform the now renamed Warfighting Acquisition System (WAS). The secretary’s new acquisition model directs services to transform today’s program executive offices (PEOs) into portfolio acquisition executives (PAEs), and it authorizes PAEs to work directly with operators to identify adequate program characteristics—even if they differ from what formal requirements documents specify. The revised WAS also allows PAEs to adjust funding between their programs to ensure they deliver viable capability in relevant time frames.14 Congress is likely to codify many of these reforms in law via the FY 2026 National Defense Authorization Act.15

Time-Based Acquisition

The DoW and congressional defense acquisition reforms reflect commercial product management practices, where development and operations often work together to field a new product that addresses a user need or problem. Rather than treating a system as finished when it is shipped, this approach assumes the product and its use case will continue to evolve as it is employed. This approach helps companies compete with rivals rather than simply recapitalizing with superior hardware to stay ahead.16

But most DoW acquisition officials still view acquisition management as a linear process that yields an enduring product. Because the new product will be hard to change, services set ambitious requirements. This forces program managers to balance between three factors often characterized as an Iron Triangle: program cost, development or production schedule, and system performance. In theory, officials can adjust the parameters associated with each factor to achieve program goals. For example, a service can reduce system performance to lower program cost, or slow development to keep program cost the same while improving performance.17

However, in practice a program office is only free to adjust a program’s development schedule. As noted above, service-defined requirements dictate performance, and departmental budgets set program cost. When ambitious requirements run up against immature technology, program managers are forced to delay development or slow procurement to stay within budget.

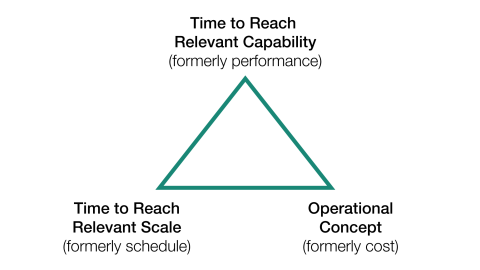

The DoW should adopt a New Iron Triangle, shown in figure 1, that is better suited to an era in which rapid technological change and the need for adaptation both allow and demand the co-evolution of technology and tactics. This approach, reflected in the new WAS, would focus more on the operational problems of the near-term instead of the projected capability gaps of the next decade.18

The New Iron Triangle flips the priorities represented by the traditional acquisition approach. Instead of performance being fixed and schedule being a variable, the WAS implements time-based acquisition in which the goal is to deliver relevant capability in a relevant timeframe. Operational needs drive the schedule, and performance becomes a variable. Funding is largely—but not completely—fixed by available budgets.

Figure 1. The New Iron Triangle

Source: Authors.

Another lesson of Ukraine is the need for relevant capacity. Innovative new capabilities cannot make a substantial impact on deterrence or warfighting if they are not fielded at scale. The New Iron Triangle would ensure that a program’s capability can be developed, deployed, and sustained in sufficient numbers to contribute, be lost to attrition, and subsequently be adapted in response to adversary countermeasures. With overall funding bound by DoW budgets, this sets up a balancing act for program managers between relevant capability and relevant capacity.

The final corner of the New Iron Triangle would enable this balance. Fixed performance requirements assume the tactics and scenario in which the system will be used. But operators will likely need to change how they fight to address an operational problem with a system that is available now at acceptable scale. For that reason, the third corner of the triangle is the operational concept for the system of systems in which the new program will be employed.

Varying the operational concept for a new system departs from current acquisition processes, but is necessary to enable identifying, developing, and fielding new systems that are acceptable and scalable within a constrained defense budget. To implement this approach, program managers and their industry partners would need to work directly with operators to identify how systems and technologies could be combined with tactics to yield the capability and capacity needed for their near-term missions. In addition to allowing for a more effective balance between capability and capacity, DevSecOps (development-security-operations) style collaboration would allow exploiting operational innovation as an element of program development, rather than only as a work-around service members employ when predicted requirements end up being wrong.19

Program offices will need to shift their management model from compliance to orchestration under the New Iron Triangle. Instead of a linear process that translates analytically derived requirements into specifications that they provide to industry, program managers will need to iterate toward an acceptable program. They will need to gather intelligence from operators about their problems and threats as well as survey industry regarding available technologies. Government teams will then need to assess potential solutions in live, virtual, and constructive (LVC) settings. And program offices will need to collaborate with operators and vendors to determine if the viable solutions are acceptable and can be deployed at scale.20

Program managers will need skills for this recursive model of program development that are different from what they use in today’s linear, compliance-focused process. Moreover, the authorities provided under the SECWAR’s directive and pending legislation will mandate this approach for most programs. Iterative acquisition may not be appropriate for long-lived capital investments like crewed ships, but these platforms comprise a shrinking portion of the US force and are infrequently replaced.

New Organizations for a New Acquisition Model

For the bulk of DoW systems, the New Iron Triangle would emphasize relevant capability and capacity to address near-term operational problems. This goal would capture the importance of adaptability, which combat operations in Ukraine and the Middle East have highlighted. Focusing on near-term operational problems is also critical to theaters like the Western Pacific, where deterrence depends on making Chinese leaders uncertain regarding US systems and concepts.21

Existing acquisition offices will have difficulty implementing a dual-track acquisition structure in which near-term solutions advance alongside long-term R&D or capital projects. After decades of reforms since the Goldwater–Nichols Act to increase jointness, adopt capability-based planning, and improve oversight, acquisition officials view themselves primarily as process mechanics rather than leaders in capability development.22 Program managers focus mostly on contracting industry performers to eventually deliver systems that meet analytically derived predictions of future need. The DoW may need a decade or more to replace today’s acquisition corps with a new generation of leaders willing to exert their authorities in partnership with commanders to solve today’s operational problems.

The DoW could accelerate adoption of the new acquisition model by standing up organizations charged with using new authorities and by directly hiring managers and leaders who can embrace new methods. But by operating outside mainline acquisition organizations, these offices will face two major challenges: (1) identifying operational partners who can help co-evolve tactics and technology and (2) integrating new programs with the rest of the force.

Each US military service includes multiple component commands working directly for combatant commanders and a myriad of experimentation organizations charged with identifying promising new concepts and technology. Rapid capability offices need to know who speaks for the operator as they pursue relevant capability and capacity in a new program. They also need to know what operational concepts or use cases are acceptable and the implications for program specifications.

Programs developed under the new time-based acquisition model will also need to be sustainable. Although developed to address a near-term operational problem, a program or modification could be in service long enough that it should be incorporated into a service’s training, logistics, and maintenance planning and execution. Rapid capability offices will need ways of either keeping near-term solutions separate from the rest of the force or incorporating them into appropriate units for the mid- to long term.

To address these issues and create a more adaptable force, the Department of the Navy (DoN) is establishing a Navy Rapid Capabilities Office (NRCO). This memo offers some lessons from other similar organizations and considers how the NRCO could be an engine for Navy and Marine Corps enterprise-level adaptation. By exploiting new acquisition models and authorities, the NRCO could be more than a stopgap measure to solve today’s urgent problems. It could show how the DoN and DoW overall could become an adaptable, learning organization that can succeed in twenty-first-century conflict.

2. False Starts Toward a Learning Force

The DoW has a long history of creating new organizations to work around existing acquisition processes. Most recently, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), Air Force and Space Force Rapid Capability Offices (RCOs), and Army Rapid Capability and Critical Technology Office (RCTTO) have been bright spots in the Pentagon’s otherwise disappointing efforts to improve operational and technological innovation. These organizations overcome cultural challenges by selecting acquisition specialists who are willing to accept more risk and exercise more agency compared to their counterparts in traditional acquisition offices. The DoW also charges them with working directly with operators in a DevSecOps-like process to understand problems and realize adequate (but not necessarily perfect) solutions in relevant timeframes.

But the DIU, Air Force and Space Force RCOs, and Army RCCTO all face challenges in enabling the pace and scale of adaptation needed to excel in modern conflict. For example, DIU has transitioned about half its prototypes into procurement contracts from the military services, an impressive amount considering the short time frame (less than 24 months) of most DIU programs. This organization also became an essential partner for military services seeking solutions from new startup companies. Without the DIU’s market understanding and engagement, the DoW would have missed numerous opportunities to benefit from these companies’ self-funded innovation.23

However, services often do not scale the programs they inherit from the DIU. In large part this is because the DIU, its industry providers, and its operational partners had not considered training, sustainment, personnel, or maintenance. The service abandons new programs that prove too difficult to integrate into its existing structures or pipelines.24 The DIU has attempted to improve the longer-term viability of its programs by working more closely with service headquarters and embedding technical experts and acquisition personnel with operational commands. Under this “DIU 3.0” model, the organization hopes to improve the ability of new programs to integrate with their host services after initial prototyping.25

The Air Force RCO has successfully brought new programs to fruition on schedule and on budget. For example, the Pentagon canceled the Next Generation Bomber in 2009 due to concerns about its ambitious goals and uncertain cost and technical risk.26 The Air Force restarted the program under its RCO, which used a more flexible approach to balancing specifications, schedule, and cost.27 Now several B-21 Raider bombers are undergoing flight testing.28 But despite this success, the RCO remains a boutique organization dedicated to a small portfolio of highly classified programs, rather than a pathfinder toward a more adaptable Air Force.29 And unlike the DIU, the Air Force RCO owns programs for the long term, rather than transitioning them to another program office.

Like the Air Force RCO, the Army RCCTO pursued a flexible approach to acquisition that has iteratively balanced capability requirements with funding constraints and schedule considerations. But also like the RCO, RCCTO also oversaw a disconnected portfolio of programs and could not be an incubator for near-term Army adaptation. For example, RCCTO included broad activities like the Rapid Acquisition Prototyping Project Office and the Advanced Concepts and Critical Technologies Project Office. However, most of its efforts were focused on a narrow set of programs for hypersonic weapons, hybrid electric vehicles, the Guam Defense System, the Multi-Domain Artillery Cannon System, human-machine interfaces, and countering small uncrewed air systems.30

The Army recently reorganized its acquisition offices to implement the SECWAR’s reforms. The Army merged RCCTO with PEO Missiles and Space to form the new PAE Fires. Although stimulated by the SECWAR’s directive, this change also acknowledges the limitations of a rapid capability office that pursues an ad hoc set of programs outside mainline acquisition organizations. Under the new construct, PAE Fires could quickly develop or acquire capabilities under the RCTTO and transition them to program offices that can sustain them for the long term. And through a dual-reporting structure, PAE Fires will work for the operational community via Transformation and Training Command and for the service acquisition executive via the Office of Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology.31

The RCCTO’s evolution offers an example of how the DoW should implement the SECWAR’s acquisition directive. Instead of treating the RCCTO as an ad hoc collection of programs, PAE Fires could use it as the innovation cell fueling its entire portfolio. This approach would avoid repeating the DIU’s failure to integrate with service program organizations. It could also help RCCTO pursue a wide variety of programs that transition into other PAE Fires program offices, in contrast to the Air Force RCO’s cradle-to-grave ownership of a few highly classified efforts.

Learning from these lessons, the DoN should consider how to make the NRCO an engine for Navy and Marine Corps enterprise-level adaptation rather than a boutique program organization or a gatekeeper to startup companies. The next section describes themes the DoN should consider in establishing the NRCO and maturing its structure and processes.

3. The Navy’s Opportunity

The DoN had resisted creating a rapid capability acquisition organization, even after the Air Force and Army established their own. The Navy stood up a Maritime Accelerated Capabilities Office in 2016, which it soon disestablished.32 In the years since, the DoN has created the Maritime Accelerated Response Capability Cell, NavalX, the Disruptive Capabilities Office, and the Marine Corps’ RCO.33 These organizations mostly assessed problems and potential solutions, but all lacked the funding and authorities to establish acquisition programs.34

The Navy is arguably the service most in need of a rapid acquisition organization. The DoW has characterized China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as the US military’s pacing challenge.35 The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has long threatened to invade Taiwan, an informal US non-NATO ally, if it pursues formal independence.36 More recently, Chinese paramilitary ships, naval vessels, and combat aircraft have been intensifying their gray-zone operations against neighbors—and US treaty allies—Japan and the Philippines.37 In an example of rising tensions, the PRC government imposed economic sanctions on Japan because that country’s prime minister mentioned that Tokyo could come to Taiwan’s defense in the event of an invasion.38

Because of the maritime nature of the Western Pacific, any confrontation between the PRC and the US and its allies will require a predominantly naval response. Navy submarines and robotic and autonomous systems (RAS) would likely play a significant role in defending Taiwan from an invasion alongside Air Force bombers.39 And other scenarios such as a blockade, quarantine, or island seizure will fall squarely on Navy and Marine units.

Beyond China, the Navy has also been leading the US defense against drone and missile attacks on Israel and shipping in the Red Sea. Houthi terrorists and Iranian military forces severely stressed Navy missile defenses through 2024 and part of 2025 with indigenous weapons built largely from commercially available components. Although the attacks did not damage any US naval ships, several merchant ships were sunk, and the Navy expended billions of dollars in missile defense interceptors.40

The DoN’s importance to the DoW’s highest priority regions and missions suggests it should be at the forefront of Pentagon efforts to field a more effective force. The DoN will need to embrace rapid acquisition to realize the adaptability that can give US forces an edge against adversaries like China, Russia, or Iran who enjoy geographic and industrial advantages as the “home teams” in future conflicts.

NRCO Should Be the DoN’s Adaptation Engine

To improve the DoN’s ability to succeed in a more dynamic threat environment, the secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) recently consolidated the department’s many innovation organizations into a single office, the NRCO, which will accelerate the delivery of systems that can arrive in the near-term, defined as the next one to three years. The NRCO’s structure and processes are not fully defined, but the SECNAV directed the office to identify five programs to induct during fall 2025.41

Analysts, former government officials, and industry leaders have written dozens of articles or reports during the last few years on how the US military should improve acquisition or speed technology adoption.42 The SECWAR’s November 2025 acquisition reform incorporates many of these recommendations, from eliminating predictive requirements for most programs to giving acquisition executives authorities to adjust funding, performance, and schedule to field relevant capabilities at scale in relevant time frames.

This memo will not repeat the recommendations of the existing literature. Instead, it will focus on ways the NRCO should diverge from conventional wisdom to provide the pace and scale of adaptation needed for the Navy and Marine Corps to deter and win modern wars.

Prioritize Adaptation over Acceleration

The other service rapid capability organizations still largely see their role as bringing new capabilities more quickly to the field. In some cases, this involves working with operational leaders to refine requirements and allow a new program to use existing technologies instead of developing something new. But often, the RCO and RCTTO simply go faster by circumventing traditional gateways and processes. Their efforts largely remain a linear process of ideation, development, and deployment.

While fielding new capabilities faster is better than going slower, the DoW’s emphasis on accelerating acquisition misses a key lesson from Ukraine, the Red Sea, and gray-zone confrontations with China: the enemy gets a vote. In a world of proliferated technology, an opponent can quickly field tactical or material countermeasures that undermine the temporary advantage afforded by a new US capability. Accelerating US acquisition processes only speeds up this move-countermove competition.

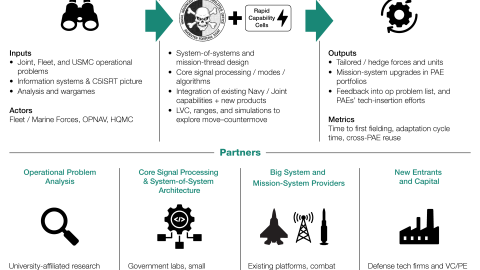

Instead of simply speeding up acquisition, the NRCO should orchestrate the DoN’s efforts to co-evolve technology and tactics. This effort would apply the SECWAR’s and Congress’s reforms to improve the pace of acquisition, but does so toward the goal of staying ahead of adversaries—or creating new dilemmas for opponents to consider. Figure 2 depicts the elements of this approach, which shares the basic DevSecOps construct common to commercial product and software deployment.

The process shown in figure 2 would rely on commanders identifying challenges or opportunities. In parallel, the NRCO would gather information or intelligence regarding relevant adversary capabilities and available technologies. Using a variety of tools and simulation environments, the NRCO and its supporting rapid capability cells (see below) would collaborate with analysis organizations and industry partners to identify promising combinations of tactics and technology that could address the challenge or opportunity.

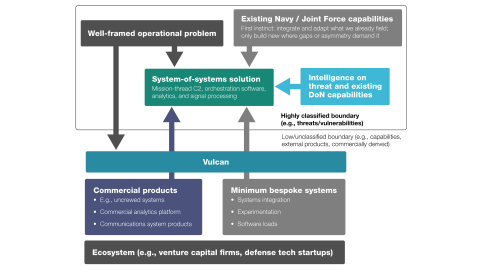

The NRCO will need a way that conveys the operational problems it seeks to address so that industry can offer solutions. The NRCO is establishing the Vulcan portal to provide this interface, based on a model the US special operations community pioneered.43 This is a good start, but the NRCO will need to ensure that operational problems are defined with enough specificity to allow industry developers to propose solutions where they can demonstrate differentiation and gain a competitive edge. Vulcan will also need to describe the eventual scale of a potential solution so that companies can determine how much time and funding to expend developing and evaluating their offering.

Figure 2. A Proposed Adaption Model for the NRCO

Source: Authors.

Operational problems will almost always demand a systemof-systems solution—otherwise they would have been solved already. The NRCO and its supporting university affiliated research centers (UARCs) and federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) will not have the time or capacity to assess each discrete element of each potential solution. Instead, the NRCO will depend on industry actors proposing fully formed systems of systems and operational concepts, including an assessment of how their solution would integrate with the existing force, its reuse of existing fleet assets, and its implications for sustainment, training, and other fielding considerations. The NRCO should grade industry offerings holistically, which could lead the Navy to prioritize solutions that do not completely address the problem but are more likely to reduce costs and be successfully adopted by the fleet.

To inform a holistic assessment, the NRCO will need metrics different from the commonly used technology readiness level (TRL). Originally developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to inform R&D decisions, TRLs do not capture important factors—such as commonality with existing systems and command, control, and communications architectures, logistics, training, or scalability—that will be important in identifying an appropriate solution to an operational problem or challenge. The NRCO should use something like the horizon level model employed by the DoN Chief Information Office (CIO). Horizon levels capture both the technology readiness of a solution as well as its ability to reach operators in a relevant time and at a relevant scale.44

Using this holistic assessment, the NRCO would select the most viable solutions for prototyping and field experimentation in concert with the relevant program office. Based on the results, the program office would scale or continue evolving the solution. The cycle would then need to start over using the adapted capability because the opponent will respond with its own countermeasures or revised tactics.

Adapting to confound adversary planning is challenging in peacetime, since there may be few interactions to demonstrate new capabilities or assess an opponent’s countermeasures. However, the DoW is arguably at war on multiple fronts. It is defending shipping and allies in the Middle East, protecting allied territory and sea lanes in the Western Pacific, responding to cyberattacks against US financial and energy infrastructure, and countering trafficking from Latin America.45 These interactions, as well as exercises and demonstrations, provide ample drivers to adapt and demonstrate Navy and Marine Corps capabilities.

Organize for Adaptation

The Navy’s response to the Houthi and Iranian missile threat provides a useful model for how the NRCO could lead DoN efforts to adapt. Navy PEO Integrated Weapon Systems (IWS) created a rapid innovation cell to develop improved approaches to defeat increasingly capable improvised drones and missiles, which are now a common feature of every militarized confrontation. This cell coordinated with operators from the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center and technicians from Lockheed Martin to analyze results from recent engagements and identify new tactics and programming for the Aegis Weapon System that would improve performance against the emerging threat.46

The Houthi threat is emblematic of how the character of warfare is changing in an era of technology proliferation. Simply having the best kit is not enough to win. A military force must constantly adapt to match its capability and scale to operational problems as they evolve. Otherwise, the superior force on paper runs out of its superior ammunition or platforms against a less capable, but more creative, opponent. Russian leaders learned this lesson the hard way in Ukraine.

The SECNAV charged the NRCO with leading the development of capabilities that would be fielded within three years. But the war in Ukraine and the Houthi and Iranian air and missile threat suggest that new or proliferated technologies could disrupt nearly every mission area. Each PEO may need to field new and updated capabilities in the near-term to keep pace with opponents—or more importantly—impose new dilemmas on them.

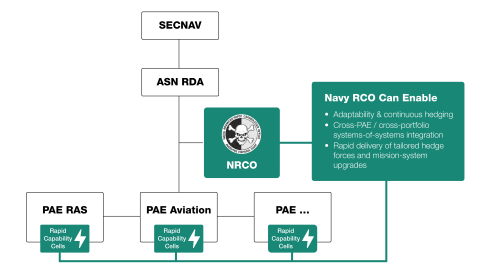

The DoN should apply the PEO IWS rapid innovation approach to systematize adaptation across the Navy and Marine Corps. The NRCO could orchestrate the efforts of new rapid capability cells in PEOs (or future PAEs) for Command, Control, Communications, Computers, and Intelligence (PEO C4I), Undersea Warfare Systems (PEO UWS), and Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons (PEO U&W), as well as the existing group in PEO IWS. The Navy’s PEOs for crewed ships and aircraft do not necessarily need these kinds of cells, since almost all of the near-term adaptation in a platform’s Figure 3. NRCO Organizational Relationships capabilities will happen through its mission systems.

Figure 3. NRCO Organizational Relationships

Source: Authors

Structurally, the NRCO should function less as a standalone program office and more as the orchestrator of rapid capability cells embedded in PEOs or PAEs. A small central NRCO staff would work with the new DoW Mission Engineering and Integration Activity (MEIA) and Navy or Marine headquarters to translate joint and naval key operational problems into new concepts and adaptation campaigns. As shown in Figure 3, rapid capability cells in mission system and RAS portfolios would then own the integration, prototyping, and fielding work for their elements of a new concept, using time-based acquisition authorities to move resources across programs and sustain a continuous test and update cycle.

The structure of figure 3 would also apply to software. The fastest adaptations will likely be new algorithms and system compositions that are driven by changes in code. As in the PEO IWS response to Red Sea air attacks, the rapid capability cells within each PEO and PAE will likely spend most of their efforts fielding new software for existing mission systems.

Under the proposed NRCO model, the DoN’s mission system and weapon PEO or PAE will encompass both traditional and new acquisition models. This will likely highlight the cultural challenges discussed earlier between traditional acquisition and adaptation. The DoN will need to ensure that both the NRCO and its rapid capability cells are staffed by acquisition officials who can embrace new models for prototyping and procurement.

In contrast, the DoN’s new PAE RAS should be completely organized around an adaptation model like that shown in figure 2. The SECNAV established PAE RAS in September 2025 to centralize efforts to develop and field RAS, which had languished for a decade due to a lack of focus.47 Although PAE RAS will inherit a few well-established programs, such as the Mk-18 and related small uncrewed undersea vehicles (UUVs), nearly all of its 60-plus projects are still developmental.48 Using an adaptation model, PAE RAS could use the flexibility of R&D programs to quickly rationalize its portfolio around a smaller set of solutions aligned to DoN or joint KOPs.

The NRCO could help PAE RAS by coordinating efforts with other PEOs to replace or evolve RAS mission systems. Navy leaders mostly consider RAS to be “trucks” for weapons or mission systems such as sensors or electronic countermeasures. To adapt Navy uncrewed systems at tempo and scale, PAE RAS will need expertise and integration support from rapid capability cells in mission system PEOs or PAEs.

Focus on Tailored (or Hedge) Forces and Units

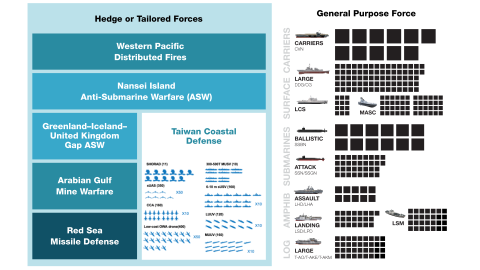

A fundamental challenge for rapid acquisition organizations, including the DIU, has been fielding systems and integrating them with the broader force. Program offices are constrained in how quickly they can modify crewed ships or aircraft due to safety, maintenance, and training concerns. And surface, submarine, air, and Fleet Marine Force type commanders need time to incorporate new tactics and systems into training and exercises for deploying units. To circumvent these potential delays, the NRCO should focus on orchestrating the development and evolution of tailored (or hedge) forces comprising mostly RAS that are designed to address the fleet’s most pressing challenges. Figure 4 describes this approach.49

The Navy should build each tailored force around a coherent operational problem and a specific threat. In practice this means the central goal of NRCO’s work is not a platform or a mission system, but an integrated system of systems and the operational concepts that employ it. Mission systems, RAS, and software are elements of that design, but they only generate advantage when they are composed into a mission thread that degrades or exploits a particular adversary kill chain.

The DoN likely needs a collection of tailored forces to address emerging KOPs. Figure 5 depicts this force design concept for the Navy, drawing upon research and wargames conducted by Hudson Institute during 2024 and 2025. For example, US and allied forces face an increasingly contested environment in the Western Pacific that will render fighters and surface combatants ineffective when defending Taiwan against a PRC invasion. The Indo-Pacific Command’s Hellscape concept— which the DoW is implementing through its Replicator initiative—is intended to help fill the gap.50 Under this concept, US and allied forces will use a tailored force of RAS to slow and degrade the PRC assault fleet. Combined with missile attacks from submarines and bombers against PLA surface warship escorts, the Hellscape concept would likely defeat at least an initial invasion attempt.

The DoN could address other KOPs using an approach similar to the one in figure 3. For example, air and missile defense in the Middle East ties up several guided missile destroyers (DDGs) that could be conducting other missions in other regions. Instead of using multiple DDGs to sustain air defense capacity in areas like the Red Sea, the Navy could deploy a single DDG with multiple medium uncrewed surface vessels (MUSV) carrying missile magazines. The DDG could preferentially use air defense interceptors from the MUSVs to preserve its own capacity. When needed, the MUSVs could cycle off station to reload while the DDG would remain in position to retain air defense capacity in theater. Overall, this concept would be less expensive than deploying multiple rotating DDGs and would free up DDGs to conduct other operations. Figure 5 lists other tailored forces for anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine warfare, and distributed fires, which are detailed

Figure 4. Tailored (or Hedge) Force Development Process

Source: Authors.

elsewhere.51 A common element of all these tailored forces is that they are composed mostly or completely of RAS to provide capacity and expendability that the general-purpose force cannot achieve within realistic budgets. However, adaptability may be the tailored forces’ most important attribute.

Because DoW leaders consider even expensive RAS expendable, they usually only perform one or two functions, in contrast to multi-mission crewed platforms that need to both conduct offensive missions and protect their crews. This allows RAS to use modular designs that have generally failed when applied to crewed ships or aircraft.52 In turn, their modularity allows RAS to change out or incorporate new features more easily than their crewed, multi-mission counterparts.

The NRCO’s highest priority role should be developing, fielding, and adapting the RAS that the Navy or Marine Corps will deploy into tailored forces. Since they are intended to solve vexing operational problems, tailored forces like the Hellscape force will be the focal point for adversary efforts to undermine US deterrence and warfighting capability. The DoW should expect that opponents like China, Iran, and Russia will quickly field countermeasures to tailored forces, which should drive the adaptation cycle shown in figure 2.

Figure 5. Proposed Future Navy Force Design

Source: Authors

Create Digital Infrastructure

As noted above, the NRCO will rely in part on industry assessments of how easily a solution can be fielded, sustained, and integrated with the rest of the force. These holistic assessments will help the NRCO and its rapid capability cells determine which solutions might offer the best combination of solving a challenge or opportunity while managing costs and complexity across the fleet.

Vendor analysis can be helpful in identifying which solutions are potentially viable, but an acquisition organization cannot depend solely on a performer’s assessment. The NRCO will need digital infrastructure to assess proposed system-of systems concepts and capabilities in the relevant operational context, as well as to speed the transition from concept to contract to fielded capability. Digital engineering offers opportunities to accomplish these goals.

For example, after an initial down-selection of the most viable solutions using vendor analyses, the NRCO could ask selected industry performers to provide their proposals in the form of digital models rather than documents. The NRCO and its partners could then assess the models in relevant LVC environments using operators to gauge both the efficacy of the solution and its ease of integration and fielding. These assessments could increasingly use artificial intelligence– enabled tools to increase the number of solution compositions and operational concepts the NRCO could review.

The DoN cannot afford to establish dedicated digital infrastructure to support the NRCO. Moreover, such infrastructure would be duplicative to existing modeling and simulation capabilities in the service and risks exacerbating existing challenges regarding the diversity of model types and environments. Instead, the NRCO should use existing model formats and a federated set of environments from the DoN’s warfare centers, UARCs, and FFRDCs.

But many new defense companies will lack the infrastructure, expertise, or clearances to build digital proposals in the government’s current formats and environments. To improve the ability of new players to contribute to Navy and Marine Corps adaptation, the NRCO and its partners should consider commercial modeling approaches such as Universal Scene Description (USD), which is widely used in animation.53 Because it is based on fundamental physics, USD provides a common framework for representing activities across air, maritime, land, space, and electromagnetic environments. Although USD does not include threat models like DoW environments such as Advanced Framework for Simulation, Integration, and Modeling, it enables performers to provide an unclassified representation of their approach using models that could be imported into other environments as needed.

Engage Allies in Rapid Capability Development

Interoperability is a growing challenge for US and allied militaries. Despite proliferation leveling the technological playing field in general, DoW weapons, communication networks, and sensors often incorporate specialized features that make them unexportable or incompatible with their counterparts from allied militaries. The NRCO could help address this problem in two main ways: by taking advantage of recent changes in export controls and by exploiting the reliance of tailored forces on RAS.

One of the main roadblocks to greater allied interoperability is legal regimes such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).54 Export controls like ITAR limit which military technologies can be shared among even US allies. And even when a company or the DoW obtains permission to share a technology, classification may prevent or constrain the degree to which capabilities are revealed.

The US government has tried in recent years to reduce the number of systems covered by controls such as ITAR.55 The most sweeping of these changes relate to the Australia– United Kingdom–United States (AUKUS) agreement. Under AUKUS, the DoW can share a wide range of sophisticated technologies, including those for quantum science, undersea warfare, hypersonic weapons, nuclear propulsion, and RAS.56

The AUKUS agreement includes two main pillars: (1) the sale of several US nuclear attack submarines to Australia during the 2030s and (2) cooperative efforts to develop cutting-edge military technologies over the next two decades. While the Trump administration recently reiterated its support for AUKUS Pillar I’s submarine sales, Pillar II’s efforts to field new technologies have stumbled due to a lack of prioritization and funding.57

The NRCO could help rejuvenate AUKUS Pillar II. Today, DoW AUKUS technology projects are distributed through numerous service laboratories, warfare centers, and defense agencies with a wide variety of sponsors. The DoN could charge NRCO with coordinating the DoN’s AUKUS Pillar II investments in coordination with counterparts in the Australian Department of Defence (ADoD) and UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). The NRCO could then align DoN Pillar II research projects with service or joint KOPs. This would help the DoW prioritize research projects and steer funding toward those that offer the greatest return on investment.

After a slow start, AUKUS Pillar II research in undersea warfare, RAS, and hypersonic weapons has made the most progress during the last two years.58 These systems are well-suited for tailored forces, which require specialized capabilities with a low personnel and sustainment footprint. The NRCO could provide a transition path for Pillar II projects by incorporating them into Navy, Marine Corps, or joint tailored forces. In addition to spurring investment in the most promising Pillar II efforts, the NRCO could use them to develop AUKUS tailored forces that address shared allied operational problems.

The NRCO could apply this same approach with allies outside of AUKUS. Crewed ships and aircraft and their mission systems are often highly classified or incorporate export-controlled capabilities. In contrast, RAS are generally modular and can accommodate a wide variety of mission systems and weapons that can include those with fewer or no barriers to technology exchange. This would allow the NRCO to develop interoperable tailored forces in concert with allies.

The DoW’s AUKUS counterparts have also established organizations dedicated to accelerating military technology adoption, including the ADoD’s Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) and the MoD’s UK Defence Innovation (UKDI).59 To improve AUKUS technology collaboration, the NRCO should collaborate with ASCA and UKDI to establish naval rapid capability cells that address shared operational challenges and opportunities.

Focus on Gathering Nontraditional Intelligence

The NRCO will need intelligence, broadly defined, to drive the adaptation process. Most discussions of innovation reform highlight how legal barriers prevent the defense community accessing intelligence community (IC) information, which can hinder adaptation at speed and scale.60 A lack of intelligence, especially via foreign material exploitation, certainly slows efforts to develop effective responses. But in the twenty-first century, the DoW has access to orders of magnitude more information via other avenues. Open-source and commercially obtained private or proprietary data can often be more valuable in assessing an opponent’s capabilities and employment concepts compared to traditional IC analysis.61

The NRCO should use an all-source approach to defining the solution space for KOPs. In addition to traditional IC information on threats, the NRCO will need open-source intelligence on the opponent’s strategies and concepts, adversary and friendly supply chains, technology surveys of potential solution providers, and knowledge of research efforts within the DoW that could be advanced into potential solutions. Industry partners can be an asset in this effort as they may already be obtaining or providing this information to the US government.

Fund Adaptation as a Priority

If adaptation is the source of future military advantage, then

Congress and the DoW should fund it as a priority. However, PAE RAS is likely to encompass programs with total funding of about $2 billion per year, or about 1 percent of the DoN’s total obligation authority (TOA).62 Combined with the funding for the Office of Naval Research and other innovation organizations, the DoN spends only a few percent of its TOA at most on capabilities that can adapt at tempo and scale.

The lack of investment is not just a challenge for solving Navy and Marine Corps operational problems. Investors in private defense companies also need the potential of a return to maintain or grow these companies’ capitalization. If the DoN does not demonstrate a commitment to innovation and adaptability, it risks discouraging new entrants or causing existing firms to focus on the commercial market.

The PAE RAS portfolio could offer an opportunity to jump-start the DoN adaptation engine. Some of its funding is tied up in development and procurement contracts, but most of it is still unobligated. The NRCO, in contrast, starts life without a dedicated budget or funding line. Given the need for NRCO to develop tailored forces that address KOPs, the DoN should consider allocating a modest amount of RAS funding to NRCO to support the mission system adaptation and integration needed to field tailored units and forces.

Over the longer term, Congress and the DoW should provide the NRCO its own appropriation, designed to implement a force design like that of figure 5. This would rebalance investment away from crewed platforms of the general-purpose force and toward RAS and supporting units associated with tailored forces. With this shift, the DoN could pursue a goal of spending up to 5 percent of its TOA, or $10 billion, on tailored forces and associated units and systems that enable a more adaptable fleet.

Establish Enduring Operational Authorities

One of the main challenges for DoW rapid acquisition offices is identifying an authoritative source to define operational problems and agree that a potential solution is acceptable. In cases when an RCO can partner with an obvious operational authority, the office sometimes lacks a collaborator in a service who can address logistics, maintenance, personnel, and training concerns that may render a solution unacceptable. And even if the office overcomes these hurdles, the service may not retain the solution because it does not address problems in other theaters.

The NRCO could avoid these problems by working with Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) or Headquarters, Marine Corps (HQMC) staff to broker a process for defining problems and assessing solutions. For operational problems with a single customer—such as US Pacific Fleet (PACFLT) for the Hellscape tailored force—the NRCO could engage directly with PACFLT to identify acceptable systems, and OPNAV largely would observe. This would allow OPNAV to assess non-material implications of the new systems that training, maintenance, or logistics organizations will need to address.

OPNAV’s role would be more central for operational problems with multiple potential customers, such as ASW tailored forces in the Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap for US Naval Forces Europe (NAVEUR) or along Japan’s Nansei Islands for PACFLT. The systems being fielded or adapted by the NRCO for these forces could be deployed to either force or for similar missions in other regions. OPNAV could help reconcile competing demands from the two relevant fleets to reduce unnecessary differentiation in these two tailored forces.

Establishing OPNAV or HQMC as the broker for operational problems and solutions would also help Navy headquarters plan future budgets. The NRCO, PAE RAS, and PEO rapid capability cells will have substantial flexibility to adjust funding between programs in their portfolio. But the overall size and categories of their budget appropriations constrain them. OPNAV and HQMC shape these investments through the DoW program objective memorandum and the proposed president’s budget.

Contribute to Joint Operational Problems

The NRCO’s most important demand signal will come from joint KOP, or those problems originated by combatant commanders that require multi-service solutions. The SECWAR’s reforms eliminated the joint requirements process, also known as JCIDS (or Joint Capability Integration and Development System). In its place, the SECWAR established a method for identifying and prioritizing KOPs. A new MEIA will manage the analytic process of identifying and assessing potential solutions, using methods such as those shown in figure 2.63

The military services tend to focus on operational problems that originate within their own operational commands, such as PACFLT and NAVEUR for the Navy. Challenges that require cross-service collaboration or capability integration are difficult and can create costs for a service’s budget without a clear institutional benefit to the service.

To incentivize services to contribute to joint solutions, the

SECWAR’s new approach creates a Joint Acceleration Reserve (JAR) to fund joint solution development or adaptation. A service can use JAR funding to underwrite development of its contribution to the joint solution, which may also support other service priorities. In this way, solving a joint KOP can provide the service with extra money to bolster efforts supporting its own operational commanders.

The NRCO should be the DoN’s point of engagement with MEIA. It should have the best visibility on potential solutions among DoN R&D organizations or industry partners. The NRCO can also ensure contributions to joint KOPs coincide as much as possible with solutions to the Navy and Marine Corps’ own operational problems.

4. Conclusion and Areas for Future Research

The Navy has a historic opportunity with the NRCO to revise its approach to innovation from simply speeding up development of new systems to exploiting adaptation as the new source of military advantage. Doing so will require DoN leaders to resist the urge to make the NRCO a boutique office pursuing a narrow portfolio of interesting, highly classified programs (like the Air Force RCO) or a disconnected collection of short-fused technical fixes and long-term development projects (like the Army RCTTO).

The NRCO should be the DoN’s adaptation engine, orchestrating the efforts of rapid capability cells in applicable PAEs to field tailored forces or evolve mission systems and weapons for crewed platforms. Working with operational commanders and Navy or Marine Corps headquarters, NRCO should manage the DevSecOps-like process of identifying and assessing potential tactical or technical adaptations. And for joint KOPs, the NRCO should be the MEIA’s one-stop shop for naval solutions.

Although in theory these roles and organizations are straightforward, they will require substantial organizational, procedural, and analytic infrastructure. For example, the DoN will need a federated set of LVC environments, modeling and simulation tools, and experimentation ranges to support the DevSecOps approach of figure 2. These systems and facilities exist today across DoN warfare centers, laboratories, and development commands, but they are disaggregated and employed for other purposes. Sustained adaptation will require harnessing these capabilities and either convincing or paying their owners to repurpose their infrastructure.

The NRCO will also require dedicated personnel and funding to execute these processes. As suggested by the experience of other rapid capability organizations, experienced program managers may be uncomfortable leading innovation rather than implementing requirements developed by others. And without resources, the NRCO will end up like the Navy’s previous innovation organizations, advocating for new concepts and capabilities without the ability to drive adaptation.

Hudson Institute will conduct a study during the next six months to explore these and other implementation challenges facing the NRCO. Although this policy memo describes a theory of success and some of its implications for the NRCO’s structure and procedures, this is only an initial concept for how the office could contribute to a more adaptable naval force. The NRCO’s most effective role, organization, and processes may need to be different than those proposed above

In its study of the NRCO, Hudson Institute will assess how to best realize the DoN’s objectives for the office as they become more concrete. This research will include how the NRCO fits into the DoN’s and DOW’s overall innovation efforts, the procedures the office should use for translating operational problems into solutions, how it engages with MEIA and Navy or Marine Corps headquarters and operational commands, and how it coordinates the efforts of DoN PEOs and PAEs.