The outcome of this month’s Camp David summit is anything but ordinary. The national leaders of the Republic of Korea and Japan met with President Joe Biden to discuss mutual commitments to fair economic practices, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and maintaining a free and open Indo-Pacific, along with rather specific and pragmatic steps to mature hard power within a tripartite regional security architecture. While such statements might seem routine, what the summit represents is the start of a political-military regional alliance architecture for Asia. And though much depends on the next presidential election, Washington's ability to seize this momentum could go a long way in deterring military aggression from the biggest threat to peace in the region and the world: Xi Jinping.

South Korea and Japan, both important democratic allies of the United States, have had to overcome vexing hurdles to get to the success of Camp David.

Before a bilateral meeting in Tokyo in March, their regular meetings had taken a decadeslong break. Despite being modern and free societies, with democratic systems of government, robust and dynamic economies, and close alliances with the U.S., historical memories are long and national and family loyalties are powerful.

The brief and oversimplified history is that Imperial Japan colonized the Korean Peninsula between 1910 and 1945, and the emperor’s regime ruled with an iron fist and forced many Korean men into labor camps and women into prostitution (the tragically titled “Comfort Women”) before and during its aggression in World War II.

On and off, as Japan transformed into the indispensable ally of America it is today, Tokyo has tried to make amends with Seoul. But the moves have largely been viewed by the families of those abused by Imperial Japan as insultingly inadequate. Adding to the prickly political dynamics, under the leadership of the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the former pacifist nation dramatically began to rearm. Japan came to terms with the threat the Chinese Communist Party-led People's Republic of China posed to Japan, the region, and the international order led by the U.S.

The charismatic, politically shrewd, and strikingly skilled politician navigated President Donald Trump better than perhaps any world leader except for NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg. Abe was tragically assassinated in July of 2022, his loss devastating loved ones and admirers who saw his leadership as key to the progress Japan was making.

Abe guided Japan toward a robust rearmament and a more prudent posture toward its own defense and deterrence with close ties to the U.S. And South Korea was not politically ready for that. China remains South Korea's biggest economic partner, and Seoul has been painfully reluctant to speak starkly about the threat the PRC poses.

This stands in contrast to South Korea's condemnations of the aggressive behavior by its northern authoritarian neighbor, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. To this point, at least publicly, security cooperation between the two Asian democracies has been defined by the shared interest in keeping Kim Jong Un under control and from firing off nuclear-capable missiles near and over their countries. And in this regard, their shared security interests were focused on collaborative efforts on the Korean Peninsula, always with the coalescing support of the U.S.

And, notably, the statement from Camp David noted the goal of the denuclearization of North Korea, not the “Korean Peninsula,” which is North Korea's preferred characterization and one the Biden administration has been willing to adopt in the recent past. The U.S.’s security guarantees to those Asian allies, not least of which the nuclear umbrella, has been the foundation of the U.S.-led order since World War II. But the U.S.’s power has declined relative to its apex following the Cold War.

And American politics are deeply unsettling to allies in the most dangerous neighborhoods, especially to those who prefer the U.S. to remain the preeminent power if the choice is Uncle Sam or Xi. But despite the insistence of Biden cheerleaders in the media and his administration, America does not always feel “back.” For example, although the U.S. is critical for the international effort to support Ukraine’s defense against Russian aggression, it has not been lost on nations such as Japan and South Korea that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s nuclear threats have prevented Washington from helping Ukraine “too much” for fear of escalation.

No doubt the efficacy of this approach has also not been lost on Xi. Wisely, allies want greater nuclear assurances. That became especially clear when South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol insisted Biden provide more robust nuclear guarantees.

But the creeping doubt in U.S. commitments isn’t tied to any one specific foreign policy matter. The entire Biden foreign policy agenda remains conflicted, with goals from climate policy to liberal domestic ideology taking precedence. Administration instincts remain more inclined toward risk aversion when courage is needed and appeasement when a matter calls for punishment. And then there is the matter of the president’s own political, legal, and health troubles. The Republican Party doesn’t offer much by way of reassurance, with no conservative internationalist candidate coming near the ethically and legally beleaguered showman, Trump.

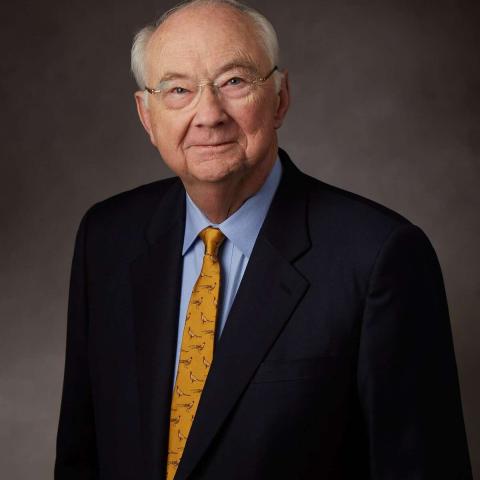

Tough times call for breakthroughs in leadership. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has carried on the legacy of Abe. What was needed was an equally committed and courageous leader from South Korea. Yoon is that man. Yoon is a conservative former prosecutor and something of a political outsider and has deftly and persistently steered South Korea toward a more muscular approach against authoritarian countries and cooperation with the U.S. and its longtime democratic neighborhood rival. His determination to move South Korea to sounder footing to deter China and deepen meaningful military ties with Japan is truly remarkable, though his successors must build on this very new progress.

And although China’s meteoric economic rise looked poised to surpass the U.S. and set the conditions for Xi to reorient the international “rules” to favor the CCP model and away from liberty and national determination, it has hit an economic plateau. But a flagging authoritarian nation could be quite dangerous, especially since Xi has tied his own fate to imperialist aims such as conquering Taiwan and pushing the U.S. out of the Pacific.

The new tripartite military plans, missile defense cooperation, and technology sharing between South Korea, Japan, and the U.S. will be enormously beneficial to convincing Xi that any aggression in the region could be met with responses that would make him regret his move. But the U.S. seems to be in the wilderness. While it works its way out, other capitals will be required to do exceptionally difficult and remarkable things, and the Camp David outcomes are Yoon’s triumph.